Universal Scene Description

I’ve been promising to write about USD (Universal Scene Description) for quite some time now, and the day has finally come.

If there ever was some top ten of worst file formats known to mankind somewhere, USD would end up ranking pretty high on that list. Perhaps even in the illustrious top three.

The unfortunate thing is that Apple decided to adopt USD as a defacto format and integrated it into its toolchains and pipelines. This in turn means that it’s impossible to avoid having to deal with it if one is making anything that is remotely portable and cross platform.

I mean it’s not an absolute mystery as to why this happened. I’ll give you a hint: Apple and Pixar. Figured it out already? I’ll give you 5 more minutes on that one.

You can find a presentation by clicking here from back in 2019. The accompanying slides of said presentation can be found over here.

If you awe a gander at the slides, you might notice this little nugget of absolute pure gold, which I have the pleasure of presenting you below:

Focus on speed, scalability and collaboration.

I’ll let you be the judge if any of it ends up ringing true by the end of this post.

Anyway, before I dive into the nitty-gritty details, I better give you a quick overview of why I ended up being involved with USD in the first place, in other words why do even I care?

Some co-workers of mine were working on a project that needed the ability to export a model into USD at runtime, for the purposes of previewing said model in an Augment Reality setting.

After taking a cursory look at the documentation, I said, well how hard can it be? I’ve done this several times before, writing an exporter is not rocket science by any stretch of the imagination.

Of course, there were some constraints; namely:

- MUST be written in C#

- MUST work as a Unity Script / Plug-in

- MUST work in the Unity Web Player

- MUST also work as a standalone command line executable (without compiling in the Unity specific bits); iterating “inside” Unity is an absolute nightmare, it’s ridiculously slow regardless of the hardware you tend to have; how do people use it on a day-to-day basis it’s beyond me, but that’s a discussion for another fine day

- MUST not have any third party dependencies of any kind

Nothing too unreasonable so far, and I hope that you do agree with me.

So, this became one of my side projects for a while and I started digging into the documentation and laying the down some of the foundations.

What I found is that in reality USD is composed of three formats, namely: USDZ, USDA and USDC.

USDZ package

The USDZ package is a container format that contains one or more USDA/USDC files, plus any other resources referenced by them; like textures for example.

As you might have guessed, the Z stands for ZIP and USDZ is nothing more than a glorified ZIP archive with another extension, which is not that unusual or bad for that matter, but as you might have already guessed there were some gotchas that I wasn’t aware of at first, which I’ll touch on later.

Nonetheless, this meant that I had to come up with a way of creating ZIP archives without any dependencies.

CRC32

While going about this, I’d like to call out a few things, one of them being calculating a compatible CRC32 checksums for each ZIP file entry.

I’ve done this by adapting the code from [bsd/libkern/crc32.c][crc32]. If you do look around online for other implementations they all seem to go into crazy-land for some reason. The simplicity of this implementation is an absolute godsend.

using System;

using System.Text;

// https://opensource.apple.com/source/xnu/xnu-1456.1.26/bsd/libkern/crc32.c

class CRC32

{

internal static readonly uint[] crc32 =

{

0x00000000,

/* full array ommited for purposes of brevity */

};

public static uint Compute(byte[] bytes)

{

uint crc = ~0U;

for(int i = 0; i < bytes.Length; i++)

crc = crc32[(crc ^ bytes[i]) & 0xff] ^ (crc >> 8);

return crc ^ ~0U;

}

public static uint Compute(string s)

{

return Compute(Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes(s));

}

}

Console.WriteLine(CRC32.Compute("hello world"));

DOS Compatible Timestamp

Another thing that came up was the need to compute DOS compatible timestamps, which I thought would be worth sharing, just in case somebody is in desperate need of it for some reason or another all of the sudden.

DateTime dt = DateTime.Now;

uint date = (uint) (((dt.Year - 1980) << 9) | (dt.Month << 5) | dt.Day);

uint time = (uint) ((dt.Hour << 11) | (dt.Minute << 5) | (dt.Second >> 1));

Do not get too discouraged by all the bit-shifting magic in there.

Alignment

Nothing too crazy so far, right? Well, this is where the madness begins, so let’s get the party going with an actual excerpt from the official documentation:

The only absolute layout requirement a usdz package makes of files within the package is that the data for each file begin at a multiple of 64 bytes from the beginning of the package.

Wait what? Exactly, that was my reaction as well. But is this is even possible?

If we take a look at ZIP specification, we can see that each “file entry” within the ZIP archive has a so called extra field length; which denotes the length in bytes of any “extra metadata” one might want to associate and store with said file entry. Any unzip tool that doesn’t care about this extra metadata can simply ignore it without having to worry about it, thus eliminating any compatibility problems.

In other words, we can (ab)use this in order to satisfy the alignment requirements by calculating the extra field length in order to align the actual data of the file entry on a 64 byte boundary starting from the beginning of the ZIP archive.

uint ExtraFieldLength = 64 - ((Offset + Filename.Length + 34) & 63);

The magic number 34 is simply the size in bytes of the ZIP file entry header.

Just swell, right? Absolutely. Oh, don’t you worry, the madness doesn’t stop just yet, or at least not until the morale improves.

It is also worth mentioning that none of the file entries within the ZIP archive are actually compressed at all; they are simply STORED uncompressed, defeating the entire purpose of leveraging a ZIP archive in the first place.

USDA

Now that I had the means to create arbitrary ZIP archives without much fuss, it was time to dig into USDA. which is a text based file format. The A in the name stands for ASCII as you might have guessed.

Quite verbose, which already made me think why on earth would you want to store a text based file format uncompressed within a ZIP archive?

It truly boggles the mind, but it is what it is. It’s too late to put the proverbial toothpaste back into the tube, I guess.

Take a look at a sample USDA file below which describes a simple textured cube.

#usda 1.0

(

customLayerData = {

string creator = "Creator"

}

metersPerUnit = 1

upAxis = "Y"

defaultPrim = "model"

)

def Xform "model" (

assetInfo = {

asset identifier = @cube.usda@

string name = "model"

}

kind = "component"

)

{

matrix4d xformOp:transform = (

(1, 0, 0, 0), (0, 1, 0, 0), (0, 0, 1, 0), (0, 0, 0, 1)

)

uniform token[] xformOpOrder = ["xformOp:transform"]

def Mesh "mesh"

{

int[] faceVertexCounts = [3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3]

int[] faceVertexIndices = [

0, 2, 1, 2, 3, 1, 4, 6, 5, 6, 7, 5, 8, 10, 9, 10, 11, 9,

12, 14, 13, 14, 15, 13, 16, 18, 17, 18, 19, 17, 20, 22,

21, 22, 23, 21

]

normal3f[] normals = [

(1, 0, 0), (1, 0, 0), (1, 0, 0),

(1, 0, 0), (-1, 0, 0), (-1, 0, 0),

(-1, 0, 0), (-1, 0, 0), (0, 1, 0),

(0, 1, 0), (0, 1, 0), (0, 1, 0),

(0, -1, 0), (0, -1, 0), (0, -1, 0),

(0, -1, 0), (0, 0, 1), (0, 0, 1),

(0, 0, 1), (0, 0, 1), (0, 0, -1),

(0, 0, -1), (0, 0, -1), (0, 0, -1)

] (

interpolation = "vertex"

)

point3f[] points = [

(0.5, 0.5, 0.5), (0.5, 0.5, -0.5), (0.5, -0.5, 0.5),

(0.5, -0.5, -0.5), (-0.5, 0.5, -0.5), (-0.5, 0.5, 0.5),

(-0.5, -0.5, -0.5), (-0.5, -0.5, 0.5), (-0.5, 0.5, -0.5),

(0.5, 0.5, -0.5), (-0.5, 0.5, 0.5), (0.5, 0.5, 0.5),

(-0.5, -0.5, 0.5), (0.5, -0.5, 0.5), (-0.5, -0.5, -0.5),

(0.5, -0.5, -0.5), (-0.5, 0.5, 0.5), (0.5, 0.5, 0.5),

(-0.5, -0.5, 0.5), (0.5, -0.5, 0.5), (0.5, 0.5, -0.5),

(-0.5, 0.5, -0.5), (0.5, -0.5, -0.5), (-0.5, -0.5, -0.5)

]

float2[] primvars:st = [

(0, 0), (1, 0),

(0, 1), (1, 1),

(0, 0), (1, 0),

(0, 1), (1, 1),

(0, 0), (1, 0),

(0, 1), (1, 1),

(0, 0), (1, 0),

(0, 1), (1, 1),

(0, 0), (1, 0),

(0, 1), (1, 1),

(0, 0), (1, 0),

(0, 1), (1, 1)

] (

interpolation = "vertex"

)

uniform token subdivisionScheme = "none"

rel material:binding = </model/material>

}

def Material "material"

{

token inputs:frame:stPrimvarName = "st"

token outputs:surface.connect =

</model/material/PreviewSurface.outputs:surface>

def Shader "PreviewSurface"

{

uniform token info:id = "UsdPreviewSurface"

color3f inputs:diffuseColor.connect =

</model/material/Diffuse.outputs:rgb>

token outputs:surface

}

def Shader "Primvar"

{

uniform token info:id = "UsdPrimvarReader_float2"

float2 inputs:default = (0, 0)

token inputs:varname.connect =

</model/material.inputs:frame:stPrimvarName>

float2 outputs:result

}

def Shader "Diffuse"

{

uniform token info:id = "UsdUVTexture"

float4 inputs:default = (1, 1, 1, 1)

asset inputs:file = @textures/diffuse.png@

float2 inputs:st.connect =

</model/material/Primvar.outputs:result>

token inputs:wrapS = "repeat"

token inputs:wrapT = "repeat"

float3 outputs:rgb

}

}

}

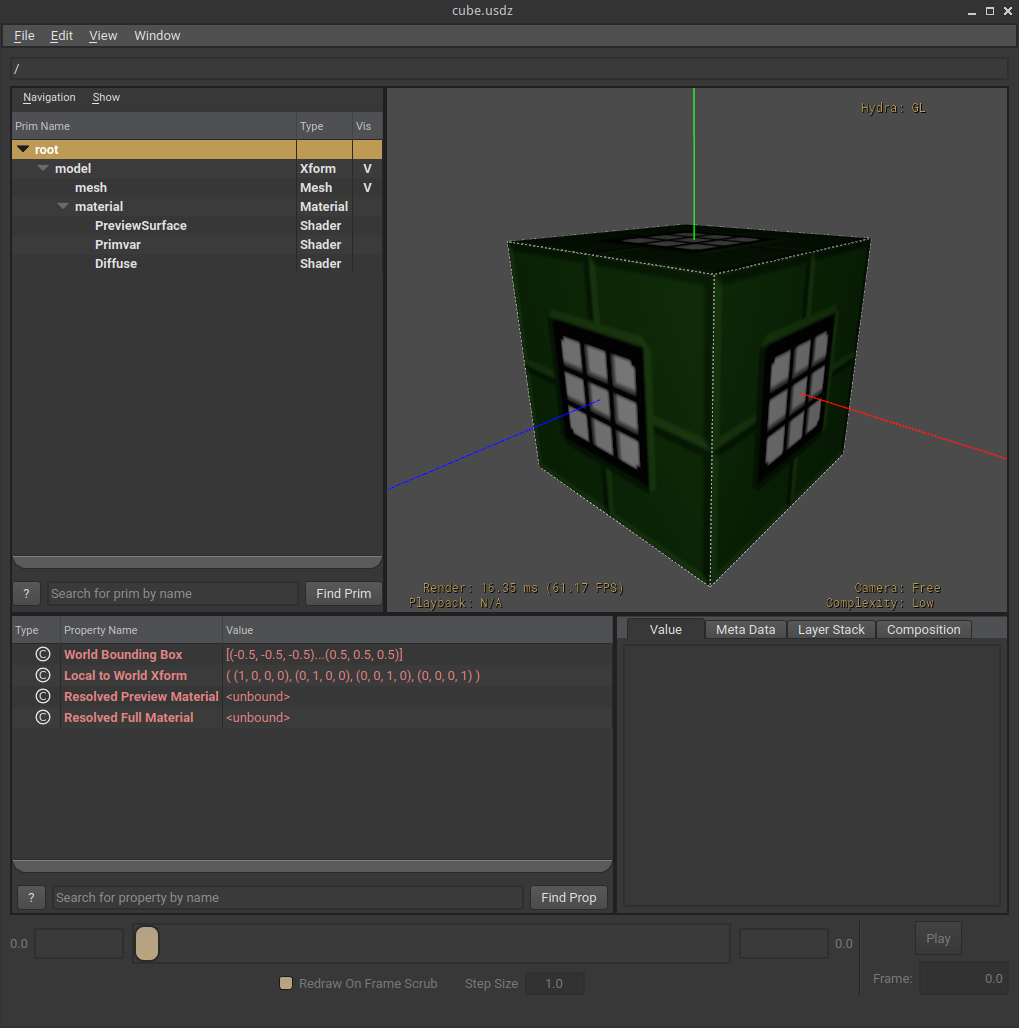

And, down below you can awe a gander at how does it actually look like when previewed with usdview, which is a utility part of the official toolkit, which also happens to contain the reference implementation of the USD writer and reader.

This text based format is documented to a certain extent and as a result it wasn’t too hard to spit out some vertices, indices, materials and so forth.

It should go without saying that the entire format has been tailored towards a PBR workflow, which is understandable, but can be confusing at first, especially when it comes to topics like “Roughness vs Glossiness”.

No matter how you slice or dice it a text based file format will always be verbose, however not all text based file formats are equal.

USDA has a lot of identifiers (keywords) and many of them aren’t very self explanatory. What even is an “Xform”? Don’t answer that, since this was a retorical question.

Another thing that is problematic is the representation of arrays. Let’s take a look at an example below.

int[] faceVertexCounts = [3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3]

While it is nice that we get to know the type and the fact that it’s an array without having to peek at the next token while parsing, the fact that we don’t know the number of elements in the array makes parsing arrays not very performant, since one will have to continuously grow the array, which doesn’t make any sense to me, especially when this format was supposed to be performant to parse and consume.

This could be improved very easily and singnificantly with a tiny change to the syntax.

int[12] faceVertexCounts = [3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3]

With this change, one simply parses out the size of the array and allocates enough memory for the entire array at once, then the actual elements can be parsed without any complications, simplifying and speeding up the entire process.

But, wouldn’t this complicate matters when it comes to writing? Not really, since you already know the number of items in any arrays that you will spit out.

Alas, in the real world you’d have to deal with way arrays that contain way more than 12 elements and without the ability to know how many in adance, your only feasable option is to just grow the array twice to its previous size (or similar) and hope for the best, in order to try to minimize the number of allocations. Which is not ideal, but it’s more and better than nothing.

You might be tempted to ask by this point if maybe a binary format would have been better, right? And you would be absolutely justified to ask that question, to which the answer is quite simple in the sense that there indeed is a binary equivalent to USDA in the form of USDC.

USDC

Now, along the way, I am pretty sure that the Vice President of Bad Ideas, might have realized that storing a text based file format in a ZIP archive uncompressed is not exactly the brightest of ideas for a number of not so hard to guess reasons, and decided to send out an email at 4:20PM on a lovely Sunday afternoon, with a single word in it that said:

thoughts?

– vp of bad ideas

And, this is how the so called binary crate format (USDC) was born (please don’t quote me on this!); which of course has support for compressed int and float arrays. Absolutely shocking, I know!

Such hardcore and revolutionary thinking. How could anyone, but a true genius and Renaissance Man come up with such an absolutely brilliant idea?

It is the most tragicomic thing I’ve seen in my entire life, and I’ve seen some, believe you me.

As one might expect, the binary crate format is not documented at all; or at least I wasn’t able to find anything and my google-fu is pretty good still; which means that the only way to learn more and untangle the format is to look directly at the open source reference implementation.

And, this is where I kind of put the project on the shelf for an elf, because I had absolutely zero motivation to try to understand and decipher it.

It’s one of the worst and most convoluted pieces of code I’ve ever seen. I am saying this with no ill feelings at all, because I’ve written crappy code in my life as much as the next person, but never ever went this far down the proverbial rabbit hole expecting to bump into mighty Neo himself along the way.

Before you start frantically searching for me on social media and call me a pretentious bastard, let me give you a tiny taste, by showing you a small excerpt below. And, if you still feel the same after you’ve seen it, then feel free to curse and yell at me like a true gentleman and scholar would on any respectable social media platform.

template <class Writer, class T>

static inline

typename std::enable_if<

std::is_same<T, GfHalf>::value ||

std::is_same<T, float>::value ||

std::is_same<T, double>::value,

ValueRep>::type

_WritePossiblyCompressedArray(

Writer w, VtArray<T> const &array, CrateFile::Version ver, int)

{

// Version 0.6.0 introduced compressed floating point arrays.

if(ver < CrateFile::Version(0,6,0) ||

array.size() < MinCompressedArraySize)

{

return _WriteUncompressedArray(w, array, ver);

}

// Check to see if all the floats are exactly represented as integers.

auto isIntegral = [](T fp)

{

constexpr int32_t max = std::numeric_limits<int32_t>::max();

constexpr int32_t min = std::numeric_limits<int32_t>::lowest();

return min <= fp && fp <= max &&

static_cast<T>(static_cast<int32_t>(fp)) == fp;

};

if(std::all_of(array.cdata(), array.cdata() + array.size(), isIntegral))

{

// Encode as integers.

auto result = ValueRepForArray<T>(w.Tell());

(ver < CrateFile::Version(0,7,0)) ?

w.template WriteAs<uint32_t>(array.size()) :

w.template WriteAs<uint64_t>(array.size());

result.SetIsCompressed();

vector<int32_t> ints(array.size());

std::copy(array.cdata(), array.cdata() + array.size(), ints.data());

// Lowercase 'i' code indicates that the floats are written as

// compressed ints.

w.template WriteAs<int8_t>('i');

_WriteCompressedInts(w, ints.data(), ints.size());

return result;

}

// Otherwise check if there are a small number of distinct values, which we

// can then write as a lookup table and indexes into that table.

vector<T> lut;

// Ensure that we give up soon enough if it doesn't seem like building a

// lookup table will be profitable. Check the first 1024 elements at most.

unsigned int maxLutSize = std::min<size_t>(array.size() / 4, 1024);

vector<uint32_t> indexes;

for(auto elem: array)

{

auto iter = std::find(lut.begin(), lut.end(), elem);

uint32_t index = iter-lut.begin();

indexes.push_back(index);

if(index == lut.size())

{

if(lut.size() != maxLutSize)

{

lut.push_back(elem);

}

else

{

lut.clear();

indexes.clear();

break;

}

}

}

if(!lut.empty())

{

// Use the lookup table. Lowercase 't' code indicates that

// floats are written with a lookup table and indexes.

auto result = ValueRepForArray<T>(w.Tell());

(ver < CrateFile::Version(0,7,0)) ?

w.template WriteAs<uint32_t>(array.size()) :

w.template WriteAs<uint64_t>(array.size());

result.SetIsCompressed();

w.template WriteAs<int8_t>('t');

// Write the lookup table itself.

w.template WriteAs<uint32_t>(lut.size());

w.WriteContiguous(lut.data(), lut.size());

// Now write indexes.

_WriteCompressedInts(w, indexes.data(), indexes.size());

return result;

}

// Otherwise, just write uncompressed floats. We don't need to write

// a code byte here like the 'i' and 't' above since the resulting

// ValueRep is not marked compressed -- the reader code will thus just

// read the uncompressed values directly.

return _WriteUncompressedArray(w, array, ver);

}

Now, I don’t know about you, but as for myself, I’d very much like to absolutely not have any code written like this in any codebase near me. Not today and not ever, and I would very much like to avoid having to work with anybody who has ever had the pleasure to write code in this manner, willingly or unwillingly.

No, I didn’t purposely pick one particular snippet (or area) in order to try to make my case. I truly wish that was the case for everyone’s sake.

To make matters more interesting, on mobile one does need USDC for obvious performance related reasons, so there’s no way to avoid having to deal with the binary create format, no matter how you slice or dice it.

The Reference Implementation

Yet another thing that you might be tempted to ask is why not just use the reference implementation as-is and problem solved, right? See no evil, hear no evil? Anyone?

First and foremost, it’s an absolute nightmare to build. Anything written in so called modern C++ is prone to severe code-rot. Even today, when compilers generally support the same feature set, it can still happen that all of the sudden a newer compiler version considers a specific thing an error, while it might have been previously valid (albeit resulting in undefined behavior) for ages.

When that happens, one has to go and dig into it and do ad-hoc fixes, which most of the time you cannot contribute back until the project itself officially bumps the supported C++ and/or compiler version, it’s just not something one would want to waste their time with. Unless of course, one got unlimited time, which I sadly don’t.

Trust me, you don’t want to be in the position of having to debug over half a million lines of modern C++ that is made worse by the absolute obscene amounts of STL sprinkled in all over the place, without any consideration at all, nor any concern when it comes to readability or performance.

I mean, just look again at code-snippet above, it should be enough to convince you to never want to touch it with a ten foot pole.

If the reference implementation would have been the bona-fide experimental passion project of someone hacking away at it in their sparetime, then I would have been more understanding and would have more than likely cut them some slack. However, this is not the case at all, and the people who produced this monstrosity should have known better in the first place.

Once again, there’s a difference in terms of expectations between something experimental and something that claims to be a “high-performance extensible software platform for collaboratively constructing animated 3D scenes, designed to meet the needs of large-scale film and visual effects production”.

Final thoughts

Avoid USD at all costs if you can. It’s not the holy grail of exchange formats that it claims to be. While attractive and well thought out on the surface, once you dig in, the cracks start to show pretty fast and it’s all downhill from there.

If you must use it, avoid the reference implementation and implement only the subset of features that you need to read/write. Infesting your asset pipeline with the reference implementation is a sure way to dig yourself and your tooling into a hole that will be almost impossible to get out of.

For an AR use-case like mine, where we are talking about a relatively low poly simple mesh with a material, it can work; but if you are exporting entires scenes, like a “level” (or chunk of a level) in an AAA grade game type scenario, then I would say that you are setting up yourself for a lot of trouble down the line.

Any format that covets itself to be some sort of an “interchange format”, in my honest opinion it should satisfy the following conditions and/or requirements:

- MUST be easy to write/read (parse)

- MUST be easy to extend

- MUST be able handle large “scenes”

- MUST not be built around a particular workflow (i.e PBR)

- MUST have a dependency free and sane reference implementation

Sadly, USD falls shorts in one way or another when it comes to almost all of these.

2023-04-29 / rant / random