2022 September Retrospective

September came and went like the wind and here I am writing this tiny retrospective up as per usual.

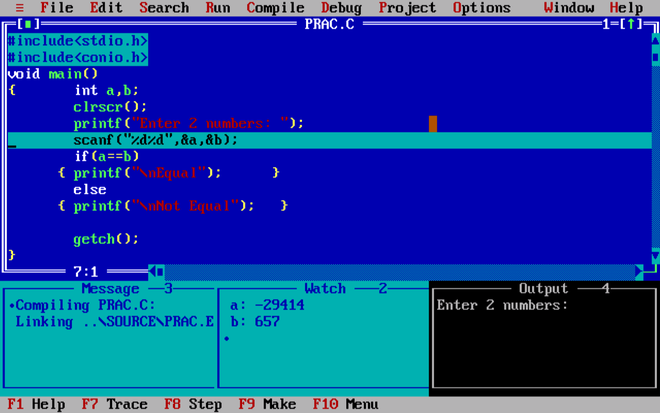

printf vs. debugger debacle

The printf vs. debugger debacle got opened again. It’s like a wound that just doesn’t want to heal for some reson, I guess?

I feel like this time, John Carmack openly talking about it on Lex Friedman’s podcast contributed to it in some way or another, but nonetheless the Twitter-verse was more than happy to jump on the opinion bandwagon once more.

It should go without saying that I am part of the printf camp, and not because I hate debuggers with a passion, or because there aren’t any good debuggers on Linux, or anything of the sorts, but rather the very simple fact that printing something in any format I want will always beat a debuggers’ built-in watch stack/variable capabilities.

And, the second reason is that printf debugging is much more convenient in many cases compared to the following ritual using a debugger:

- set the initial breakpoint

- launch the debugger

- run & step around while watching the stack/variables

- profit?

Now, I do understand that if you got a large project, written in a terrible language like C++ (orthodox C++ is still plenty terrible!), coupled with a terrible and slow build system, then having to recompile the project every single time can be very very time consuming, in which case even with the additional steps, using a debugger will make more sense and will undoubtedly be faster. But this is not a scenario that I personally have to deal with, thus using a debugger is simply more trouble than its worth for me.

And, yes I did use the Borland/Turbo Pascal & C/C++ IDEs in my youth which had a built-in and very convenient debuggers. It still made no real difference to me.

One additional thing that came to light during this debacle that I just cannot comprehend, and that is the an argument that goes something like this:

“Oh, I must use a debugger, because whenever I have to work on a new code base, I heavily rely on a debugger in order to understand said code base”.

Biggest load of bull that I ever heard in my life, period! Well, if you are part of the club that uses this argument, you should seriously reconsider your choice of career, or perhaps it’s time for you to take your leave and retire. Pick up carpeting or gardening maybe?

And, that will be the last thing I’ll say about this for now. Y’all just have to agree to disagree wit me when it comes to this subject.

OLEN Games Toolkit

This month yet again I continued laying down the foundations for the OLEN Games Toolkit and focused on figuring out how to implement error handling.

When one thinks about error handling, without involving so called exceptions that are known to cause permanent brain manage after prolonged use, one usually will land on something that looks like the snippet below:

enum

{

OLN_RESULT_SUCCESS,

OLN_RESULT_OUT_OF_MEMORY,

OLN_RESULT_INVALID_ARGUMENTS

};

int oln_init(const int argc, const char **argv);

int result = oln_init(argc, argv);

if(result != OLN_RESULT_SUCCESS)

{

// ...

}

This approach of course is what led to the now rather infamous ERROR_SUCCESS, which should be familiar to the true old timers like myself.

In addition, this approach usually will have an auxiliary helper function which allows the user to turn the error code into an actual error message.

const char *oln_result_message(int result)

{

switch(result)

{

case OLN_RESULT_OUT_OF_MEMORY:

return "out of memory";

// ...

}

return "no error";

}

// ...

oln_log_printf(

OLN_LOG_TYPE_ERROR,

"error: %s",

oln_result_message(result)

)

Another variation on this theme is to use a global last error, which is usually thread local to store the last error in, which then can be retrieved when necessary.

oln_error_set(ERROR_SUCCESS);

// ...

int err = oln_error();

if(err == ERROR_SUCCESS)

{

// ...

}

Some take this further and have a “stack” of last errors, like OpenGL, while others sometimes end up combining these approaches, a prime example of this would be the Win32 API.

What all these have in common is the fact that they all rely on specific and unique error codes, which is fine if you are writing a specialized API of some description, but not ideal for something more akin to a framework of sorts. Why? Because one has to make sure that user defined error codes are unique, and do not collide with anything provided by the framework itself, which very easily can turn into a nightmare, especially more so when the code base is modular and a certain “bring your own” kind of an attitude is encouraged.

There are various ways to mitigate this. The Win32 API for instance uses one bit out of the 32 bits of the error code to indicate that the error code is a user defined one.

So, let’s take a look at what I ended up with and dive into the nitty-gritty details of the matter at hand.

typedef struct

{

oln_opaque_t opaque;

} oln_error_t;

#define oln_error_make(message) \

(oln_error_t) { .opaque = (oln_opaque_t) message }

// ...

const oln_error_t *oln_error_invalid_arguments = &oln_error_make(

"invalid arguments"

);

bool oln_init(int argc, const char **argv)

{

if(argc < 2)

{

oln_error_set(oln_error_invalid_arguments);

return false;

}

return true;

}

// ...

if(!oln_init(argc, argv))

{

const oln_error_t *err = oln_error();

oln_log_printf(

OLN_LOG_TYPE_ERROR,

"init failed: %s",

oln_error_message(err)

);

// ...

}

Calling oln_error is guaranteed not to return a NULL pointer, and once called it will also clear the last error. Therefore, calling it again will return an error with its message set to no error.

What about checking for specific errors? Well, one can just compare the extern globally defined constant compound error literals.

extern const oln_error_t *oln_error_inalid_arguments;

if(!oln_init(argc, argv))

{

const oln_error_t *err = oln_error();

if(oln_error_is(err, oln_error_invalid_arguments))

{

// ...

}

// ...

}

Isn’t this a bit verbose? Yes it can be. In order to get around this, one can also just pass in NULL to oln_error_message in order to grab the latest error message without the need to call oln_error first. Useful in cases where all one wants is the error message itself.

if(!oln_init(argc, argv))

{

oln_log_printf(

OLN_LOG_TYPE_ERROR,

"init failed: %s",

oln_error_message(NULL)

);

// ...

}

Okay, but what about the case, when it’s simply not practical or desirable to define a constant compound error literal for some reason or another?

// sets the internal message pointer to the

// provided string literal

oln_error_set_message("failed to open file");

// sets the internal message pointer to the

// provided pointer; this means that this pointer

// must remain valid outside of the current "scope"

oln_error_set_external_message(strerror(errno));

// makes an internal copy of the formatted (sprintf) message

// this doesn't allocate from heap, it will simply truncate

// the message if it happens to be longer than 4096 characters

oln_error_set_formatted_message(

"failed to open `%s' for reading",

filename

);

Furthermore, oln_error_set_formatted_message can also be used to wrap an existing error in order to provided more context when bubbling an error up the chain.

oln_error_set_formatted_message(

"failed to open `%s`: %s",

filename,

oln_error_message(NULL)

);

And that’s about it. I feel like this offers enough flexibility without the need for error codes and rather obscure non intuitive return values. Time will tell if this was the right call, or if I end up regretting it once a non trivial amount of code has been written using this style.

2022-09-30 / retrospective