2022 August Retrospective

This month I ended up focusing some of my spare time on laying down the foundations for the OLEN Games Toolkit, and taking Ghidra on test-drive of sorts.

OLEN Games Toolkit

The language of choice is C of course. Which shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone who happens to know anything at all about me. C11 to be more precise, which should be relatively well supported and implemented at this point by all major compilers.

In order to give you a taste of where I am headed with this, let me give you a concrete example of how the API looks and feels like.

Let us take a look at the implementation header below.

#pragma once

#include <oln/foundation/types.h>

typedef struct

{

uintptr_t opaque;

} oln_file_t;

#define oln_file_is_open(self) ((self)->opaque != 0)

oln_file_t oln_file_open_read(const char *filename);

size_t oln_file_read(oln_file_t *self, void *buf, size_t size);

void oln_file_close(oln_file_t *self);

Please note how there is no #ifdef OLN_FILE_H guard and #pragma once is used instead.

Also, there are no system wide includes in this header file.

The only include is <oln/foundation/types.h> which contains the following:

- base type definitions like

uintptr_torsize_t - helper macros like the quintessential

OLN_CONCAT(a, b) - preprocessor defines like

OLN_WINDOWSfor compile time platform, architecture, etc. detection

In other words, the bare minimum, which keeps things fairly lightweight and easy on the eyes.

And now, let us awe a gander at the actual implementation:

#include <oln/foundation/file.h>

#include <stdio.h>

oln_file_t oln_file_open_read(const char *filename)

{

return (oln_file_t) { .opaque = (uintptr_t) fopen(filename, "rb") };

}

size_t oln_file_read(oln_file_t *self, void *buf, size_t size)

{

return fread(buf, sizeof(uint8_t), size, (FILE *) self->opaque);

}

void oln_file_close(oln_file_t *self)

{

fclose((FILE *) self->opaque);

}

So, what do we see here? First of all, we include our file.h header first, and then any system wide headers, in this case only <stdio.h>. Which means that system wide types, etc do not leak outside of the implementation scope.

Second, we cast the opaque FILE * pointer we get from fopen to an opaque uintptr_t. But wait, why are we returning by value? Isn’t that one of the 3 cardinal sins of programming in C? Yes and no. In this particular case, there’s absolutely no difference, since both FILE * and uintptr_t are of the same size and will fit in one register.

As a bonus, this also gives us some extra type safety compared to a good old fashioned regular opaque pointer.

And, the last thing to note is how we cast this opaque uintptr_t back to the opaque FILE * pointer as needed.

Last but not least, let’s take a look at how one would use this API below:

#include <oln/foundation/types.h>

#include <oln/foundation/log.h>

#include <oln/foundation/file.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

oln_file_t file;

size_t n;

uint8_t buf[4];

if(argc != 2)

{

oln_log_printf(

OLN_LOG_TYPE_ERROR,

"usage: %s file",

argv[0]

);

return -1;

}

file = oln_file_open_read(argv[1]);

if(!oln_file_is_open(&file))

{

oln_log_printf(

OLN_LOG_TYPE_ERROR,

"failed to open `%s' for reading",

argv[1]

);

return -1;

}

n = oln_file_read(&file, buf, sizeof(buf));

if(n != sizeof(buf))

{

oln_log_printf(

OLN_LOG_TYPE_ERROR,

"failed to read %lu bytes (got %lu bytes instead)",

sizeof(buf),

n

);

oln_file_close(&file);

return -1;

}

oln_file_close(&file);

return 0;

}

Not bad at all? Right? I think so too. Obviously, nothing is set in stone just yet, but this looks nice, clean and extend-able as far as I am concerned.

One thing I am still on the fence about is whether I should call it std instead of foundation.

#include <oln/std/types.h>

#include <oln/std/log.h>

I will be posting more about this as things continue to evolve in the coming weeks and months.

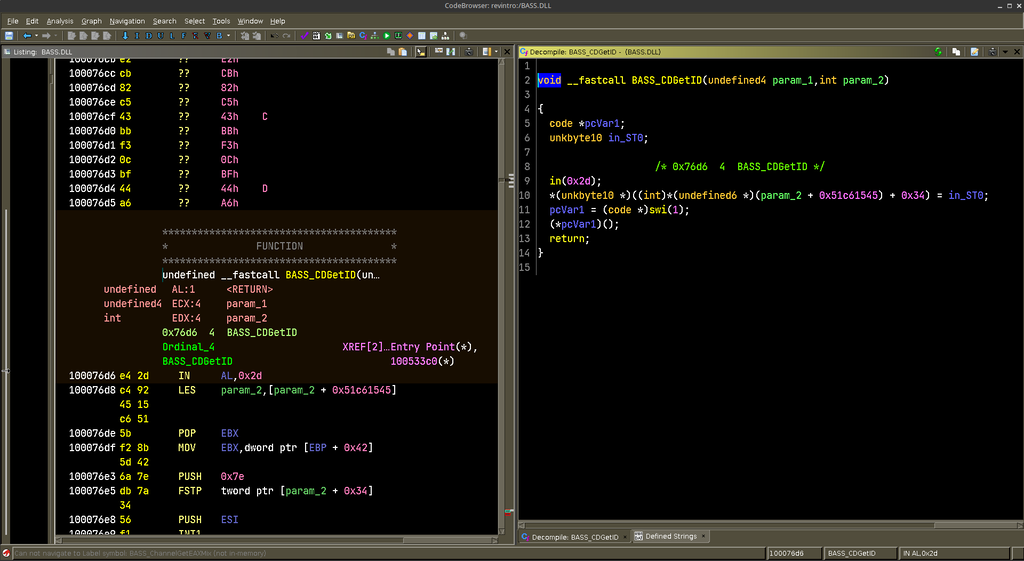

Ghidra

Reverse engineering applications, games and various file formats used to be one of my favorite pastime activities in my younger years.

Whenever I wouldn’t be coding, I would most certainly be looking for patterns with a hex editor in some file of a game or an application.

While I don’t wander into this territory quite often these days, I still find myself quenching my thirst for patterns every blue moon or so.

In the early days, some of my tools of trade were W32Dasm and HView (quite typical at the time), then later in the early 00s Olly Debugger, which was an absolute god-sent for me personally. A true game changer and in many ways still undefeated when it comes disassembling and/or modifying (patching) 32-bit executables on windows in my humble opinion.

A year ago or so, I started doing some digital clean-up (I am a digital hoarder to a certain extent) and I stumbled upon some remnants or perhaps I should relics of my reverse engineering era, which turned the fire in my belly up a notch.

Due to this, I did a quick search to see what are people using these days for dissembling executables and that’s how I stumbled upon the almighty Ghidra, developed by the NSA.

I took a quick look at it and it seemed like everybody and their grandmother is using, especially in so called cyber-security circles (whatever that means!).

Then of course, in my usual way got side-tracked and never really ended up doing a deep dive so to speak, until earlier this month when I finally decided to give it a go.

One of the most valuable features of Ghidra is the ability to see a decompiled view of the disassembly, which makes things a lot easier to parse and skim through. Reading unannotated assembly produced by a compiler is vastly different experience from reading hand crafted assembly, which makes the decompiled view an absolute gem.

Another great feature is the ability to “parse C source code” and auto-determine structures, types, etc, however it’s not as easy as it might sound to please the “C parser” plug-in, therefore most of the time you’ll find yourself that you have to massage things by hand, etc. This is one of the areas that I’d love to see some improved.

Speaking of things to improve, the experience of patching (entering assembly instructions) could also use some more love compared to the absolutely amazing experience provided by Olly Debugger.

I will not go into some of the other features, but all in all it is truly a one stop shop when it comes to both analyzing and patching binaries.

Don’t want to make any promises just yet, but I might end up doing a series of streams / videos focusing on reverse engineering, as I already set my eyes on more or less the perfect target for such a thing.

2022-08-31 / retrospective